READING: THE STORY OF FILM BY MARK COUSINS (CHAPTER 2)

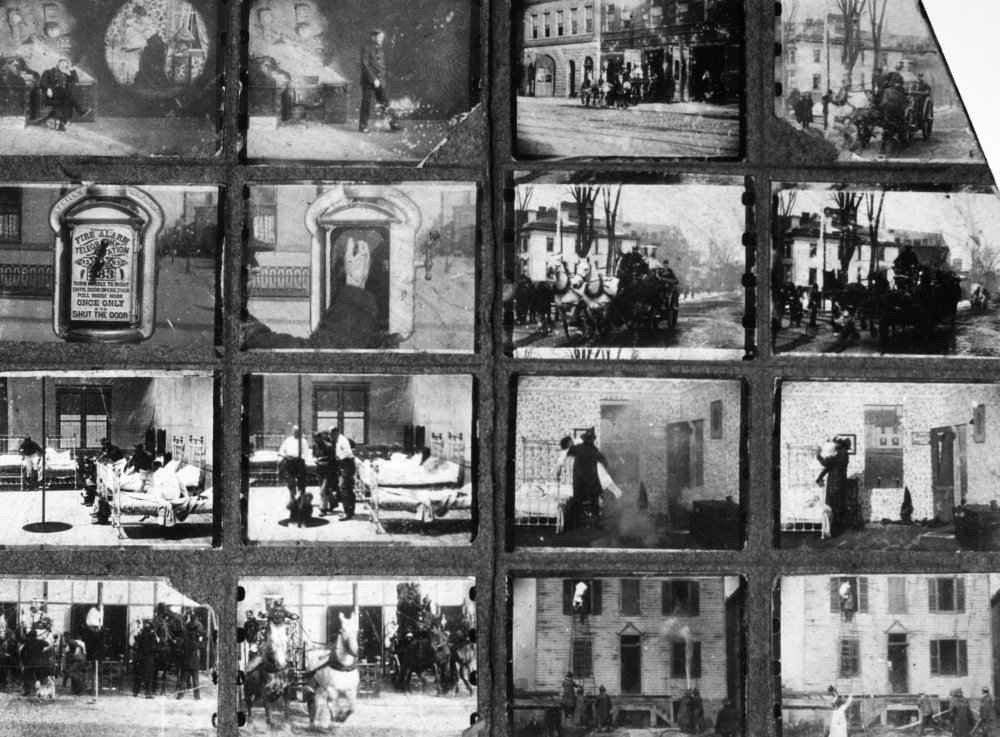

VIEWINGS: The great train robbery (1903), life of an american fireman (1903), those awful hats (1909), the birth of a nation (1915), cabiria (1914), intolerance (1916)

Apologies for the late entry this week, but the holiday did make it difficult to get in as much viewing and reading as I would have hoped (some of these movies are long, man). But you’ll be happy to know that while I’m not coming in on time with my post, it’s also not even about what I promised it would be in last week’s post!

After finishing the recommended viewings and readings for Unit 1 of this course, I decided I wanted to spend one more week in this early period of film before diving into expressionism and the height of the silent era, moving us from the 1900s and 1910s into the 1920s. What I found particularly interesting about Unit 1 was that film had its roots in spectacle rather than narrative, and I wanted to dig a little deeper to understand how and when the pendulum swung towards narrative. Turns out it didn’t take too long.

By the end of the first decade of the 1900s, the language of cinema had started to become established. It was interesting to watch the very first uses of some of the most basic tools to a filmmaker like cross cutting (fancy word for cutting between things that are happening at the same time), or continuity editing (fancy word for cutting to a different angle of the same action or scene). These techniques feel so obvious to us today, but over 100 years ago, when film was largely mimicking theater, filmmakers needed to consider these types of moves heavily to avoid jarring audiences (audiences comprised of the same people who thought the train was going to burst out of the screen 10 years prior).

^ the first use of continuity editing, Life of an American Fireman (1903)

These types of techniques introduced the tools filmmakers use to confer narrative, but they were developed out of necessity in order to relay their increasingly intricate thrill rides. A filmmaker might say “what’s another experience you’d never get in real life that we can render on the screen.. A train robbery!”, but to render a train robbery they had to come up with some new tricks to make it feel like a train robbery. Thus cross cutting is born, and longer narrative storytelling is possible in the medium. This continues to snowball as we get into some of our first narrative features.

The features I watched for this Unit were The Birth of a Nation (1915), Cabiria (1914), and Intolerance (1916). I’ll take this moment to say that I won’t be commenting in depth on the abhorrent, destructive, and lethal real-world intentions behind the first film, and instead will focus in this blog post on the film’s significance to film history. The political context of Birth of a Nation deserves a post of its own, and that’s not the focus of this series, so I will try to put it aside after this paragraph, but suffice it to say this film is evil and sinister in its nature and has done more damage to the United States of America than any foreign enemy ever could have done.

^ the Lincoln assassination in Birth of a Nation

The first features of this course do bridge the gap between a pure thrill ride and what we understand today as a ‘movie’. Birth of a Nation is really centered around a few of what we would now refer to as ‘action sequences’. We have the civil war battle scene, Lincoln’s assassination, and the final raid scenes. To elevate these spectacles, we have a plot that presents characters we’re supposed to care about, so we feel the emotional stakes of what is transpiring in addition to the spectacle. This is really the root of all that film is, so it’s neat seeing some of the first few big swings at it (not to mention the technical innovations).

Speaking of technical innovations, Cabiria (1914) was a pleasant watch. I included it, programmed before Intolerance (1916), because the it was cited as a direct inspiration for the latter film. Cabiria is renown for its set design, which I will admit I was also pretty enamored by (I was also enamored by what I imagine was the #1 buffest person alive in 1916, playing Maciste. Seriously, this dude looked like Arnold in the 80s but before they even had modern gyms — but I digress). Again we are presented with a narrative to accompany our ride through this exquisitely rendered historical epic. I do think this film had the least effective narrative of the three, but there are some moments where the sets are so big and intricate, it really makes you wonder how the heck they pulled this off over 100 years ago.

^ Maciste, the absolute dawg

Finally, clocking in at number 232 on the Sight and Sound top 250 movies of all time, D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance. I was interested to see Griffith come back after Birth of a Nation, having been inspired by Cabiria (and frustrated by the response to Birth of a Nation). I’ll have to say that while I have some issues with the movie (briefly detailed on my Letterboxd review), there are some sequences that are really effective. The spectacle of watching a raid of Babylon, or just the crane shots of Babylon in general were amazing for 1916. The tension he creates in the modern story before the climax is also ahead of its time. This movie might not crack my personal top 100 but you can see how it lays the building blocks for a lot of what’s to come.

^ the Intolerance Babylon set

And with that, we’re gonna officially move on to Unit 2: The Silent Era and Expressionism (for real this time, I promise).

Leave a comment