READINGS: Italian Neorealist Cinema: an Aesthetic approach by Christopher Wagstaff

VIEWINGS: Bitter Rice (1949), Rome, Open City (1945), Paisan (1946), Bicycle Theives (1948)

Bawn Jor No! Welcome back to the Loosely Scripted Film Course. This unit covers Italian Neorealism, the movement in Italian Cinema immediately following the end of WWII. I’ll start out by mentioning that I was really knocked out by Christopher Wagstaff and this unit’s reading. With the exception of A Short History of Film, I’ve found many of the readings to be really dense and sometimes dry. Wagstaff’s Italian Neorealist Cinema, however, reads pretty briskly and is absolutely jam-packed with really interesting concepts on film theory as well as great practical insights into this specific movement.

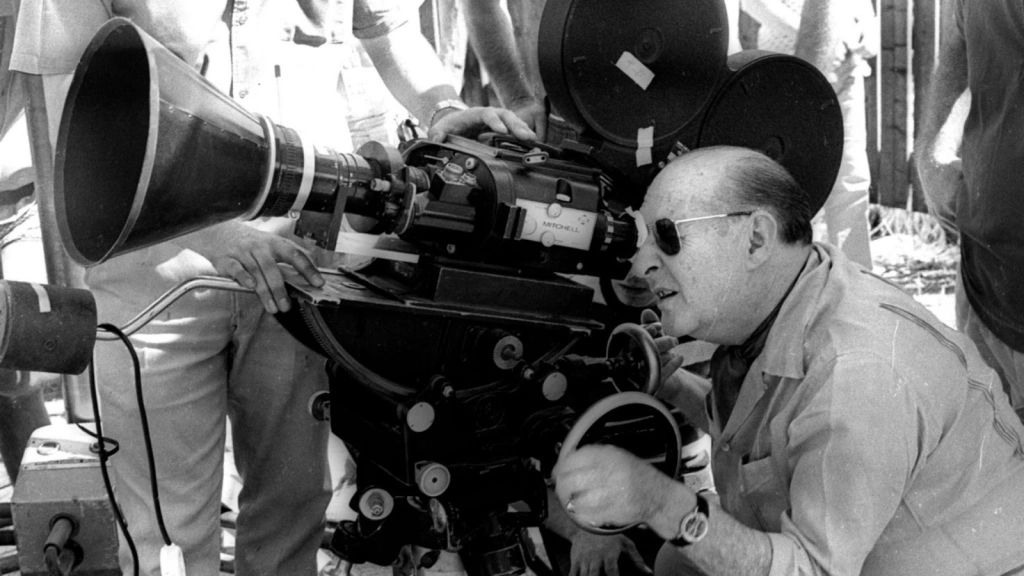

The book begins by contextualizing the Italian Neorealist films in their historical setting. In the wake of WWII, the Italian film industry (in addition to presumably every other industry) was in total disarray. The studio system had been destroyed, either by way of literally-destroyed infrastructure, or by economic turmoil that left studios with extremely limited resources. Filmmakers were left with two choices: exit the film industry in search of more traditional labor, or take to the streets and make films outside of the studio system. The films made by those who chose the latter option were made on shoestring budgets, using limited equipment, nonprofessional actors, real locations (often with no permits), and guerrilla filmmaking tactics.

The films they made took on a ‘realist’ tone and style in part because of these limitations. Grand spectacle was simply not possible to film on the budgets and scale these filmmakers were working on. So instead they made films about what was around them – mainly poverty stricken compatriots and their war torn nation.

While necessity is the obvious reason for the stylization of these films, Wagstaff also points out that the filmgoing public in Italy at the time was a public wrestling with its own identity. They were emerging from the grips of fascism and facing down new ideas such as communism, and while the nation was coming to terms with its recent past, it was also rejecting the types of escapist entertainment pedaled by its former fascist government. These lighthearted melodramas and comedies featuring the Italian elite were no longer of interest to a public that felt so far away from that identity when they were struggling to feed their families. So the neorealists arose to offer an alternative – films about the working class struggle that felt like the real life the Italian public was experiencing.

Understanding the historical context in which these films were produced and consumed is crucial to understanding the movement and the films themselves. For me, the realist style often blurred the lines between narrative fiction and documentary filmmaking – particularly in films like Paisan, which chronicles several stories anthology-style and captures ground level life for civilians during the war. Bitter Rice even opens with a documentary style talking head explaining the rice fields in northern Italy and the seasonal migration of the women who come to work in them.

Far and away the most famous and acclaimed film in the Italian Neorealist canon is Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves, which comes in at #41 on the current BFI Greatest Films of All Time list. The film chronicles a man who stumbles upon one of the most elusive and sought-after resources that could befall a man in post-war Italy – a job. When the security and stability that this could bring his family is taken from him, he goes to greater and greater lengths to try to get it back.

The film does embody the staples of the neorealist movement. The performances from the non-professional actors all throughout the movie are really unbelievable. It uses very simple, but effective, shots of the streets of Rome – basically no sets or production design outside of what’s found in real life. It tells a very grounded and contained, humanistic story rooted in the most basic motivation of a man seeking desperately to provide food, shelter, and a good life for his family. It documents an aspect of real life in postwar Italy that many real people were facing. While it actually ended up not being my personal favorite of the neorealist films I watched for this unit (that title goes to Paisan), I can understand why this gets thrown in as the exemplary neorealist picture. It manages to land like a real movie movie while actually balancing all of these production difficulties and tackling these difficult real-world themes.

That’s all for now on Italian Neorealism. I really enjoyed these and added a few more to my watchlist, I’ll look forward to getting around to those. My next unit will cover Japanese cinema, which is especially timely with the recent release of Assassin’s Creed: Shadows and upcoming release of Ghost of Yōtei, two video games set in feudal Japan. This will be an exciting look into some less-western cinematic history, so look out for it soon!

Leave a comment