READING: A Short history of film BY wheeler winston dixon & GWENDOLYN AUDREY FOSTER (CHAPTERs 2 and 3)

VIEWINGS: kid auto races at venice (1914), return to reason (1923), the gold rush (1925), the cabinet of dr. caligari (1920)

This week, I delved a bit further in depth and chronology into the early history of movies. As I’m running out of the short clips that qualify as films that were more prevalent before the mid 1910s, the number of viewings was smaller this week, but I think the two shorts (Kid Auto Races at Venice, and Return to Reason) mirror the point that is made by the feature length films in this unit fairly well. The point in question being that American cinema in this period was focused on cranking out hits (commercially and financially) while global cinema was more of a vehicle for individual artistic expression (the seeds of this phenomenon were planted much earlier, as discussed in Unit 1 of this course)

I found the readings this week to have lots of interesting nuggets that ultimately come together to form the central idea stated above. Chapter 2 of A Short History of Film covers what’s going on in America during this time, which really gives a new appreciation for the first hour or so of Damien Chazelle’s Babylon (I promise I won’t mention Babylon every week, but it’s relevant in these early units). I do wonder what the American film industry would look like without Thomas Edison. Without him, “The Edison Trust” probably never gets formed which means that much more independent filmmakers can operate freely in the states in those early years without fear of being sued out of existence by Edison for use of his tech. You wouldn’t have as many filmmakers fleeing as far away as possible from Edison’s headquarters in New Jersey, landing in the then-sleepy town of Los Angeles, California. You also wouldn’t have what Wheeler Winston Dixon refers to as the ‘assembly line’ method of film production, where he was churning out movies like Model-Ts.

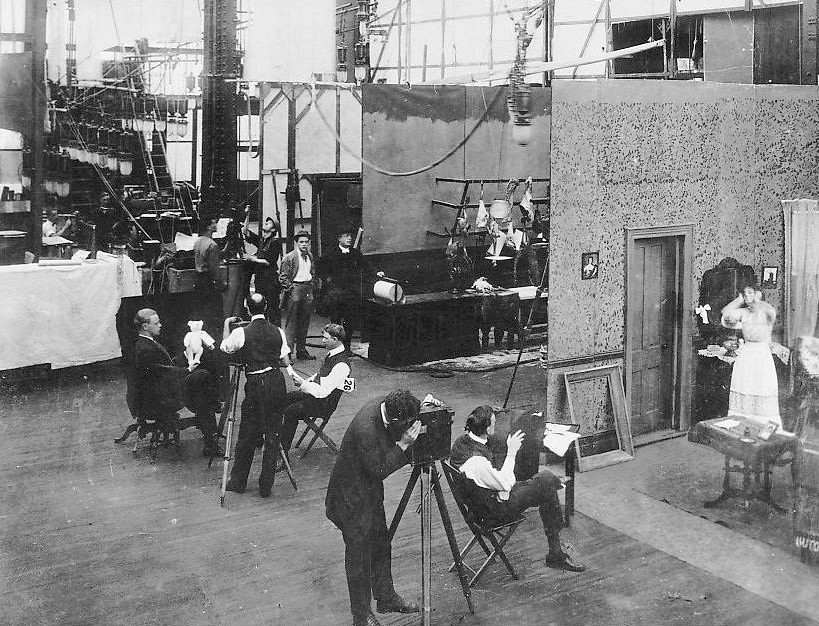

^ several films being produced simultaneously

Edison did, however, jump start the American film industry by identifying it as a lucrative business. Other countries did this as well, but the rapid and sharp commercialization of the industry seems to have been uniquely American. Other than the prolific output of similarly styled films, the marker of the American industrialization of film was the shady business practices that filmmakers and producers were engaging with to make their films, and make them hits. Being in Los Angeles, but with financial backing in New York, some filmmakers would cash a check in LA from a bank in New York with nothing in their account. They would take the money, rush produce a short film, stick it in theaters and use the box office takings to cover the check by the time it got back from New York (gotta love the snail mail). One producer, Carl Laemmle, led a campaign to denounce the rumors that their newly poached star from a competing production company – Florence Lawrence – had died in a streetcar accident (a rumor that Laemmle had started himself). True Billy MacFarland – Fyre Festival level scammery.

As for the films themselves, I understand why we wanted to program and read about international cinema during this time. The movies aren’t bad – as a matter of fact I quite enjoyed Charlie Chaplin in The Gold Rush (1925), reprising the character of “The Little Tramp” that was started in the 6-minute short Kid Auto Races at Venice. The reason to branch out from American cinema from this time period is that the American films just aren’t as interesting, from a film history perspective. Similar to how you might see something like Vortex (2021) and say “wow I’ve never seen a movie like this” (check out the trailer) but you might see the latest Fast and Furious entry and be like “yep, that’s a Fast and Furious movie alright”. It’s not that Vortex is better than Fast 9 (though it probably is), but it’s just more interesting. Lots of American movies then and now can’t afford to be interesting because of the hundreds of millions of dollars at stake – they can’t afford to take the risk. Lots of foreign filmmakers don’t have that burden.

This takes us to our second feature film for this unit The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920).

This slightly steps on our next unit, explicitly covering German Expressionism, but I think it was a worthwhile watch for this unit (though you could have probably done just as well watching something from France or Russia during this time). You can basically trace all of what makes up the ~vibes~ of horror cinema for the next 100 years back to this movie, or at least this movement in early German film. The hyper-stylized set and costume design, the melancholy nature of all the characters, the twist ending (sorry to Chris Finke if you’re reading this, but now you know that there is a twist) – it all builds up to something that just isn’t replicated in American movies until much later. Which is an important note: it is replicated in American movies. Anybody who’s seen anything directed by Tim Burton will instantly recognize the style used in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Not to say that the films wouldn’t be important if they didn’t influence American filmmakers, but if you’re a casual movie fan and thus your primary interest in movies is in American contemporary filmmaking, the reason you should care about Dr. Caligari is that you will see this style iterated on in your favorite movies and those movies shape the direction of Hollywood (and thus the culture at large). No Caligari means no Batman (1989); no Batman (1989) means no The Dark Knight (2008); no The Dark Knight means no Avengers: Endgame.

Next week we will dive more headfirst into the style used in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari in Unit 3: German Expressionism. See you then.

Leave a reply to Loosely Scripted Film Course Unit 4.5: Sound and Color and Censorship, Oh My! Landmarks of the 1930s – Loosely Scripted Cancel reply